SciArt Residency Blog #12, Dec 2, 2018

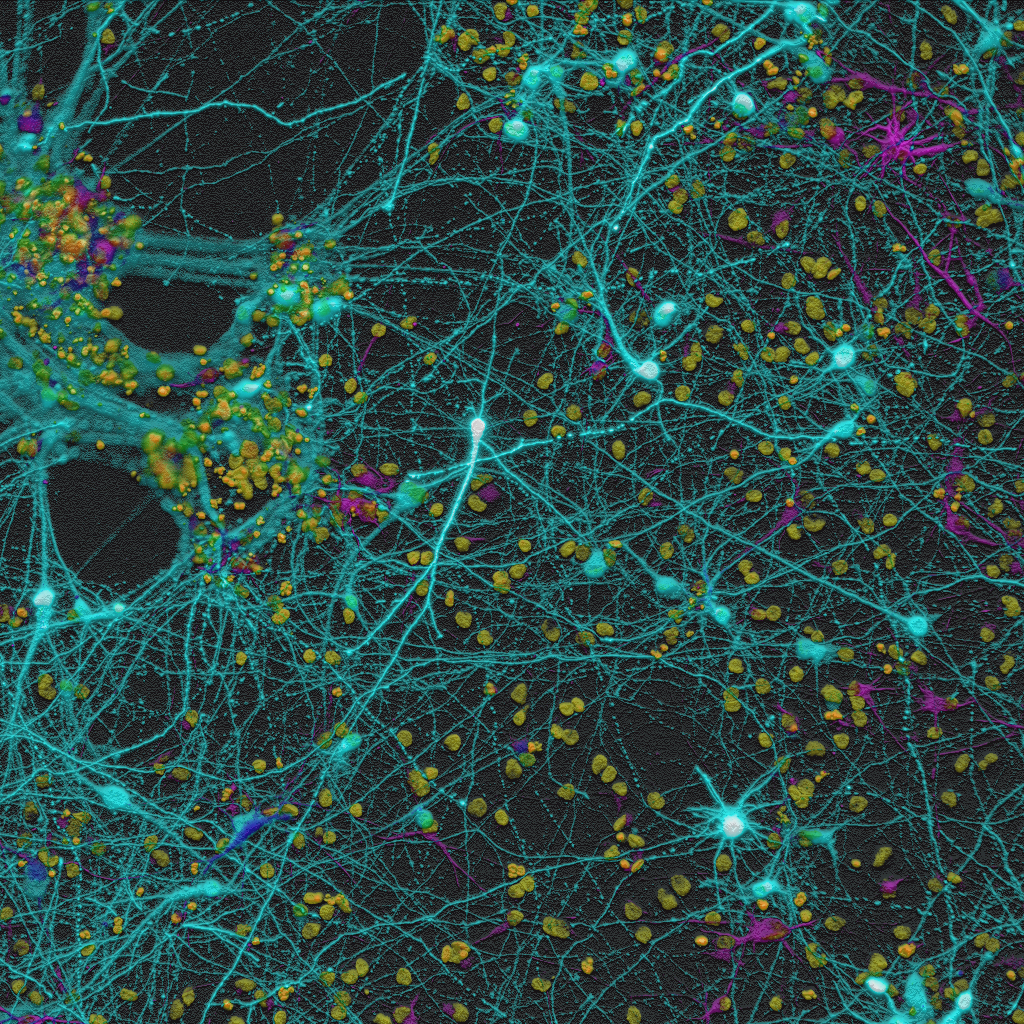

“Mapping Manhattan”, collaboration between Yana Zorina and Darcy Elise Johnson, microscopy, digital media

“ Mapping Manhattan Revisited”, by Darcy Elise Johnson, 36” X 36”, acrylic inks on wood

The weeks have passed quickly and my painting (Image #3) is nearly finished. My original decision to paint on wood with acrylic inks is because the wood grain has an organic pattern that interacts with the overlying image. I chose inks because they are transparent and sink into the wood in a satisfying way, acting more like a stain than opaque paint. Inks are also fragile and yet always leave their trace on the wood. Once laid down it is impossible to completely erase them. This requires careful painting and decision making throughout the process.

Although I have never used fluorescent or metallic inks before, I was drawn to them for this piece because of the brightness of the digital image that Yana and I began with (Image # 1). Digitization injects light into an image, making it more luminous than it is. I wanted to somehow mirror that brightness. The interesting thing is that the fluorescent pigments will slowly lose their luminous quality as they fluoresce away their excitability to UV light. The neurons were “artificially” stained before Yana imaged the culture with an electron microscope. (Image #1). I took this image a step further, digitally, to arrive at “Mapping Manhattan”(image #2). Using our respective art techniques, Yana and I are each bringing this scientific image into the realm of the artist.

Looking at the artwork Yana and I are making brings me back to the idea of scientific models I talked about in Blog # 10 (November 16th.) In some ways, Yana’s beadwork and my painting are both abstract models of the original image. In my piece (Image#3), I was fairly careful to render it accurately yet it is still less complex than the original. Details are left unresolved, helping to emphasize the main structures. To be useful in explaining complex phenomena, a model must pare down information to its essentials. The model can then make the overarching characteristics of something, such as a network of cells, more accessible to any viewer.

Another important aspect of scientific models is the ability to manipulate various dimensions. In the Week 11 Blogs of Diaa & Stephanos, Stephanos presents his mathematical model of neuronal activity in memory. Mathematical models expand our ability to visualize processes and events that our brains are not capable of holding onto in ordinary circumstances. This type of modelling is a powerful simplification because it allows us to then manipulate variables and that our conscious minds would lose track of within several mental operations.

Scientific models use the same technique as artist’s images in simplifying and emphasizing specific aspects of phenomena. If all details are included in a “scene”, we get lost in the noise. Sensory processing in the brain also plays that role for us by directing our attention to the salient details around us from moment to moment and then constructing a model of that experience in our brains. The model becomes a memory which may be altered repeatedly over time in the process of being stored, retrieved and stored again.

Our brains need this sorting to take place to direct our attention to the most essential aspects of an experience. Once the basic structure of a memory or knowledge about the world is formed, we can more easily embellish it with more detail. Learning through time and experience requires us to redesign or reorganize the model, often increasing its scale and complexity. But it must start simply. I have learned this from teaching.

So if the model creates the structure within which new information and experiences can fit, then the role of the artist and scientist is to create a compelling, accessible and comprehensive model or image that the viewer can take away and refer to later, developing it further with their future experiences. Again, I would like to point to the Beholder’s Share.